There are treasures nestled among the rafters at Aung Soe Min’s downtown Pansodan galleries in Yangon, where paintings crowd the walls and huddle in tight stacks crammed into every corner. Here old boxes burst with the memories of a nation. There are movie posters from a fleeting age of freedom, before army rule shattered Myanmar’s cinemas, city maps from earlier days under the British and glossy magazine adverts promising a gleaming prosperity that never arrived.

But there is no chance that dust will settle on these relics from a half-forgotten past, or the man who has spent a lifetime preserving them.

Aung Soe Min breathed life into Myanmar’s contemporary arts scene when censorship was at its height and mentored a new generation of creative talent. He was regularly hauled in by the authorities for questioning over his work, particularly as the junta launch sweeping crackdowns on expression following the 1988 mass uprising against the government, although he managed to escape prison.

Now he is on a one-man mission to awaken an interest in arts and history that was deadened during decades of military rule, when soldiers trained their guns on the history books and museums echoed with the self-justifying shouts of propaganda.

With a laid back style that belies his incredible energy, he juggles more projects at any one moment than most people take on in their lifetimes. His latest is the Open History Project, which aims to show history without fear and give ordinary people access to their shared past through local photographs, documents and ephemera.

“Our own path, the very ground that we stand on, is our history.

“Without knowing history well, we will not have creativity. We should understand what spirit drives our society. You cannot copy down words from a textbook and build a country.

“There is a deep connection between arts and society. From the 1980s to 2010s, we descended into the age of imitation. Everyone sang plagiarised songs. It was the same in the movie industry — Thai movies, Indian movies, Chinese movies were all imitated. If we could not create our own arts for 20 years, then surely there was something wrong with our society?

“How are we going to survive and stand on our own if we keep doing this? We will lose confidence in our society when we cannot create our own arts.

“I dreamed of being an artist since I was a little kid. I wanted to paint. When comic books were popular, I wanted to be a comic illustrator. Apart from my time at school (he studied mechanical engineering at a Government Technical Institute in central Myanmar), I was devoted to art. I wrote movie scripts, published books and directed movies.

“I knew most of the artists. A lot of painters had to depend on the publishing businesses, like magazines and periodicals. They did illustrations for them. There were few artists who could live on the sales from their paintings.

“The industry was like that from 1980s to 2000s. There were no well-known artists.”

At the time the most common Myanmar paintings were concerned with pastoral and traditional scenes, or with images of monks. Artists who wanted to diverge from those themes would often come up against the authorities.

“Censorship back then was very strong. Sometimes the authorities wouldn’t allow too much red in a painting. They prohibited yellow when they thought it indicated the saffron revolution. There were so many cases like that.“

“I was never jailed but was frequently interrogated and there was disruption whenever I wanted to work.

“In 1988/89 I opened a library and they wanted to detain me. They didn't say it was because of the library but it was an attempt to stop me from doing it and I had to flee. I was only about 18 then.

“There were also disruptions when I tried to organise literature festivals. I was questioned during the Saffron Revolution and a few of my friends were arrested. But the harassment stopped after I opened the gallery and focused more on the arts. I was still engaged in micro-politics in the arts.

“When we started Pansodan Gallery the country was closed off to so many things. There were no buyers outside of our circle of friends. We started in 2007/8. We opened after the Saffron Revolution. Preparation took a long time. It was definitely a time of struggle.

“We did not want just a gallery, we wanted to start an art movement. We started poetry competitions, discussed issues relating to peace and ran shows like Myanmar Muse that showcased Myanmar women’s traditional outfits. We organised about 50 shows in the first year and more in the second year. That way, we generated interest and media coverage.

“Since then similar galleries have popped up. I think the art gallery landscape has changed because of this.

“Before when we were unhappy with the government, we took to the streets. We protested. Right now, we can relay our messages through arts. So paintings become something more than inanimate objects hung on the wall. They express messages and feelings. Our galleries took part in the movement in that way. These are the changes.

“I want art in every corner in my country. I want people to know that art can exist around them, whether at home or in the office or restaurant or at the monastery. We plan to promote the arts in the cities and in the villages. In the future, there will be more museums. That will help people improve their creativity.”

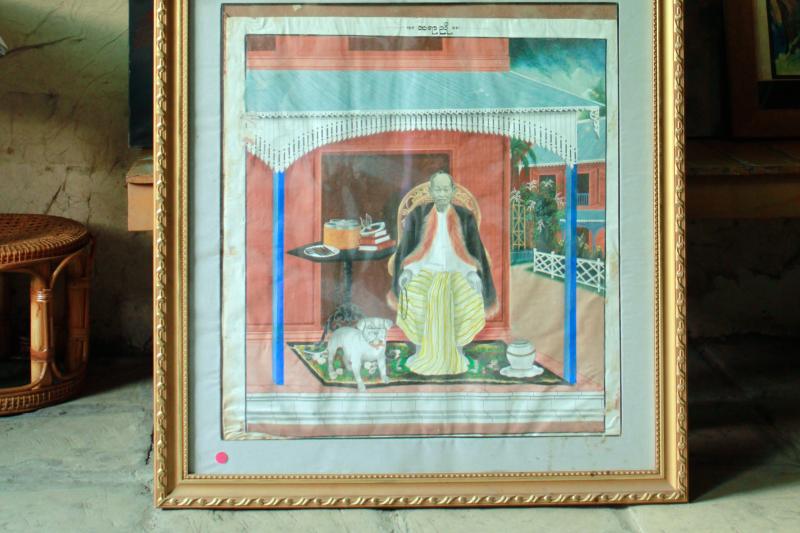

We asked Aung Soe Min what his most treasured item was and he pulled out this painting from the early days of British colonial rule.

“I liked this painting as soon as I saw it. It’s very special and totally unique. There are many better paintings or more perfect ones, but this is my favourite. We are trying to trace back society (and this is a) vivid image about this time.

"It is from the family of the man (pictured). They could not maintain it anymore so they sold it to me. And I just keep it.

“It was painted in the 1890s at the beginning of colonial rule for the whole country. This is when Burmese people were trying to adapt to the new rules and new economic systems of the British.

“Burmese people didn’t use perspective before and you can tell the artist is learning about it, but it’s not quite right yet. Everything is very surreal. It’s one of my favourite paintings. There are maybe more perfect paintings but this one tells many stories. That’s why I like it so much.

“The hat was normally a symbol for a wise man or an official in the 19th century, but one interesting thing is that he has put his down. It can mean he is relaxed, not in his office hours, but at the same time he is showing off the bulldog and also the fur coats, maybe to show he is in English government service.

“His face and the dog are in black and white -- this is the influence of photography, which was new to Burma at the time. When photographs were first shown to the public people would be shocked. Maybe they thought they saw a ghost.

“It’s very important for people to take care of their past, their ideas, their fashion or their feelings, that kind of thing. That’s why museums are important. I really wish museums were a part of our society and people could see them as a mirror, a reflection and a spiritual connection between old things and new things.

“Most of the real history lies among the people.”

(Interviewed in November 2015 and again in October 2016)