The author is a journalist from Shan State, and they are receiving support from The Kite Tales to write these diaries.

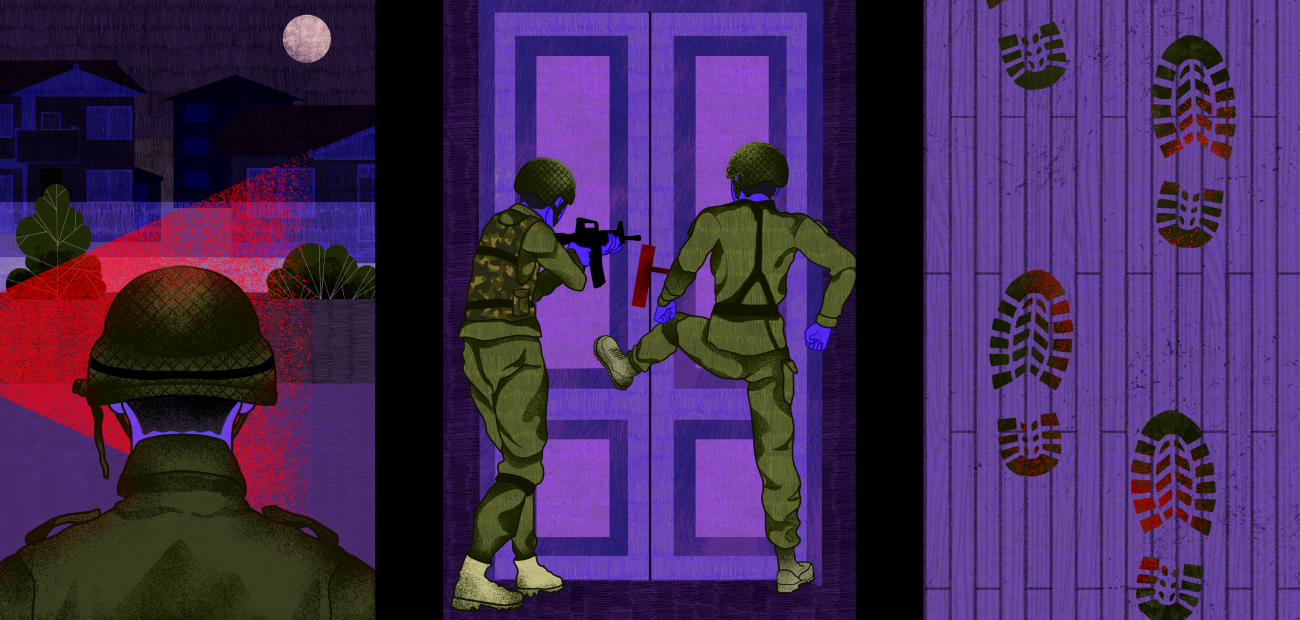

The No. 1 police station in our northern Shan State town was bombed soon after the coup. This triggered nighttime house-to-house searches throughout the area by soldiers and police. They arrested anyone they deemed suspicious and sent them for interrogation.

The night they reached our neighborhood, local people called and messaged each other frantically. Everyone kept tabs on where the raiders had reached and which house they were inspecting. As they closed into our neighbourhood, phone calls stopped, and only short text messages were exchanged.

We could hear them kicking doors and shouting as they approached our house a little after 11 p.m. They demanded that every house open its doors. If people didn’t comply, they would kick the doors open.

Since I am a journalist, I feared that if they checked my phone, they would find something incriminating. So, I turned off both my phones and hid them inside a sack of rice. Then, I slightly lifted the curtain to peek outside. They were shining flashlights into the houses they were about to inspect, calling out for people to open their doors. Everyone was terrified, turning off their lights, locking their doors, and staying silent.

Around 90 soldiers arrived at our house and two neighboring houses. They yelled with their guns raised.

“Is anyone inside? Open the door!” they shouted. It was already 11:30 p.m.

Suddenly, they were pounding on our front door, yelling, “Open up! Otherwise, we’ll shoot!”

The door was shaking violently. Fearing they would fire, we had no choice but to open it. Right in front of me stood a soldier aiming his rifle directly at me. When I looked outside, I saw that many soldiers had already entered our yard. I had no idea how they got in since we never opened the gate for them.

The soldier pointing his gun at me shouted angrily: “Why didn’t you open the door sooner? We could have just shot you. We need to check your guest list.” (Under an arcane rule enforced through decades of military rule, people in Myanmar are technically required to register overnight guests with local authorities)

“Why are you conducting inspections at midnight? Can’t you do this at another time?” I demanded.

“We work day to day just to survive. We have to wake up at 4 a.m. to go to work. Unlike you, who get paid salaries at the end of the month, we have to work hard just to afford our next meal.”

One of the soldiers muttered: “We’re just following orders.”

There were around 40 soldiers in our yard. I couldn’t see their badges properly, but there were officers among them. There was also one police officer, but no neighborhood administrators, only military personnel.

Others were searching the houses next door, with about 20 soldiers in one and others checking another adjacent house.

Although they claimed to be checking the guest list, they were also rummaging through goods in front of our house. They pulled off the plastic covers protecting new tires from the rain and asked: “What are these for?”

It was obvious they were brand-new tires. I felt a surge of anger but kept my voice calm.

"They're new tires. They're not mine. We just transport them,” I explained. “We only earn 100 or 200 kyats per tire, at most 800 kyats."

Then, they started opening the back of our transport truck, which was loaded with goods for the market, including vegetables, kitchen supplies, furniture, and agricultural tools. They pulled them out and tossed them aside without saying what they were looking for.

I was furious but tried to stay composed. I approached the police officer standing nearby.

"Sir, we only earn a living by transporting goods for others” I said.

“These aren’t even our goods. We only make a small amount per trip. During COVID, we couldn’t work for months. Now that we finally can, we just want to make an honest living."

Meanwhile, the soldiers stormed into our house with their boots on, rummaging through every room. Since our house was near a university, we rented out rooms to female students.

One girl, who had been organizing protests in her neighborhood, had been staying in our house that night because the police were looking for her in her own neighborhood. Knowing the military was conducting house-to-house searches, she had been hiding on the upper floor.

As they checked the guest list, they ordered all the tenants to come out. Because of COVID, the university was still closed, so there weren’t many tenants. The girl who had been hiding came out first, followed by one of the three tenants. The other two were too scared to come out and hid under their beds.

Luckily, they seemed preoccupied with finding the culprits behind the bomb attack who are believed to be young men so when she came out, we were being questioned, and they didn’t scrutinise the household list so closely to check if the names on the list correspond to the people here. So she got out of trouble.

They then started checking phones.

I followed them into the kitchen, my heart pounding. I had hidden my phones and laptop, but I was worried they might find them. A few nights before, young protesters had left some protest materials in my room, including printed posters and alms bowls. At night, they would hold flash protests with these materials.

Having heard about the planned house searches in advance, I had hidden most of the alms bowls by wrapping them in paper and mixing them with plates and kitchen supplies. But I had forgotten to remove the covers of the bowls. So, just a few hours before the soldiers arrived, I had an idea. I turned those alms bowl covers into plant pots by putting soil and placing potted plants on top.

Back in the kitchen, I was nervous but relieved that they hadn’t found anything. Then, four or five soldiers had entered my room to search.

I braced myself, holding my breath as the soldiers searched my room. I had stacks of A4 sheets filled with protest messages.

My room was cluttered with goods, textiles, books, and other items. The protest sheets were hidden between fabric rolls. But then I realized my mistake - I had forgotten to remove the "Press" sticker from my motorcycle helmet. Worse, my work desk had notes related to news coverage, and right there on the table was a copy of the 2008 Constitution and American Center’s Civic Education lessons.

They picked up my helmet. My heart sank when they noticed the "Press" sticker.

One of the junta soldiers who saw my helmet shouted loudly: "Is there a journalist in this house? Who is it?"

"It's mine," I answered, forcing myself to sound calm.

At that moment, while they were looking at the 2008 Constitution book and the Civic Education files on the table, I noticed the notes I had written for the next day's news coverage at the edge of the table. I quickly grabbed it and slipped it into the back pocket of my trousers.

Unfortunately, they found my old notebook from before the coup. I couldn't deny it. They took the notebook.

"Those are old notes from a long time ago,” I said.

“I haven't written news in a while. These are just notes from early 2020."

They flipped through the pages one by one. They didn't say anything. That was a relief.

Then, they opened my luggage and searched through it. They found over 400,000 kyats hidden between my clothes and some papers clipped together. One of the soldiers snatched it away and asked what it was for.

I had heard that the junta soldiers who raided a house up the street had taken a bank book with about 6 million kyats in it from a wardrobe drawer.

"That money isn’t mine,” I said. “It’s for buying goods and I can't afford to pay it back."

I took it back.

Then, things took a turn for the worse. They started pulling down tote bags that had protest leaflets hidden inside. At that moment, I thought to myself: "This is it for me tonight."

Just as they were pulling down the second bag, they found a toy basket. It was full of toy guns. They tossed the basket aside, scattering the toy guns across the floor.

I was afraid they would find the protest leaflets. So, while trying to cover up the scattered bags, I said: "They're just toys. The boys in this house only play with toy guns."

Then, they barged into the kids' room without taking off their boots. The two children were already asleep. I said, "There are no other men in this house. There are only boys."

When I stepped outside, I saw the officer still standing in the same spot, talking to my sister. He was calling the soldiers who were still searching upstairs to come down and leave. But they didn’t seem to be listening.

On the upstairs balcony near the water tank, some of the soldiers continued searching.

Then, they called me over.

As I walked up, I saw the two kids’ water pipes and toy guns, which they had set up as water shooters.

"The kids made that. They were just playing," I told them.

Throughout the entire search, none of the soldiers took off their boots. Even the ones upstairs didn’t bother coming down the stairs. Instead, they jumped over the brick wall into the neighboring house.

When I came back downstairs, my cousin's phone was still being searched. I stood next to the soldier and said: "What did you find? There’s nothing in his phone. He doesn’t even go out except to drive."

"There’s nothing, but the CCTV footage we’re looking for shows a motorcycle similar to this one," the soldier replied.

He then pulled out a printed photo showing two men on a motorcycle.

"These two were the ones who threw a bomb at the police station. They have tattoos on their legs. We are looking for them," he said.

I told them to go ahead and check everything.

They checked the bike thoroughly, even opening the tool compartment. They found nothing. But they confiscated the slingshot and some stones.

When the soldiers finally came outside, I followed them. They ordered us to unlock the front gate. They had jumped over the wall to get in, but now they wanted us to open the door for them to leave. I wanted to say, "Just leave the way you came in," but instead, my sister and I unlocked the gate.

I saw that the whole street was surrounded. There were two civilian cars and about seven military trucks parked outside.

Just then, the neighborhood administrator arrived and greeted us. The administrator spoke to us in a friendly way, and the soldiers’ attitude changed slightly.

"We’re just doing our duty," one of them said.

When they finally left, I checked the time. It was past 1:30 a.m.

After they were gone, neighbours from the front and side houses came over to talk about what had happened.

At the house in front, there was an old woman and her grandson. The soldiers didn’t enter through the gate but jumped over the wall. They surrounded the grandmother’s small hut, some entering through the door while others climbed through the walls.

The grandmother had told her grandson to hide behind the door, but the soldiers found him. They slapped and kicked him for no reason. They even made him take off his shirt and pants and kicked him with their boots.

The grandmother cried and pleaded repeatedly.

"He was just visiting me because I'm sick,” she told them. “I can't walk. I have a fever. I need him with me."

The soldiers only left when they found nothing.

As for the house next door, there was only a drug addict living there. When the soldiers entered, he started giving them cigarettes and talking with them. They also took some instant noodles from his kitchen.

Up the street, three young men were arrested and released about three hours later when the soldiers apparently realised they had caught the wrong people.

I knew that being searched at gunpoint in the middle of the night was unjust, but there was nothing I could do.

Luckily, the soldiers didn’t realise that I was a freelance journalist for a news outlet the military junta had outlawed soon after the coup. I had also continued working for an authorised news agency.

That night I felt like I barely escaped the jaws of the tiger.

Artwork by Songbird who is receiving support by The Kite Tales to produce illustrations.