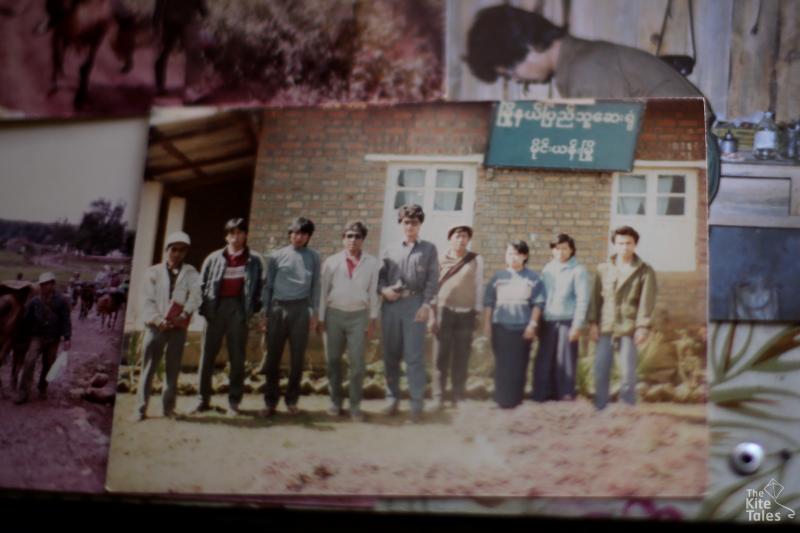

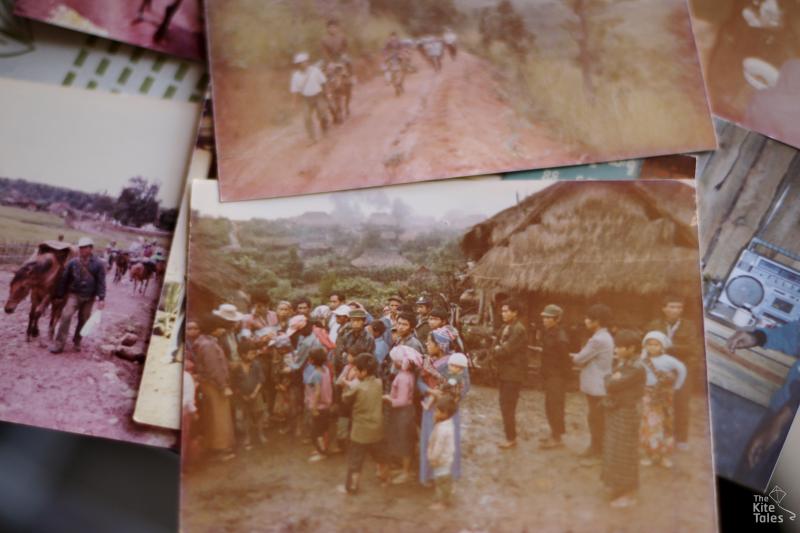

Laying out yellowing photographs from his youth, Kyaw Thu Latt creates a montage of the life and unexpected exploits of an accidental adventurer. Some of the faded prints show a tousle-haired young doctor treating patients in Myanmar’s Wa territory -- the secretive enclave of the country’s most powerful ethnic armed group and its biggest drug traffickers. In others he is riding a donkey on a dirt track, or posing with a motorbike, sunglasses on.

While he may appear sanguine in the pictures, Kyaw Thu Latt looks back on his time providing medical services in some of Myanmar’s wildest borderlands with surprise and amusement.

“When I was young, I lived quite softly. I didn’t like roughing it,” he said of his childhood in Bilin, Mon State.

But as the two-decade-old pictures show, life did not turn out the way he had planned.

Kyaw Thu Latt was in the Shan State capital Taunggyi, working on disease control for the government health service when a phone call came in that there was an outbreak of cholera in the Wa areas.

Located along the border with China and controlled by the feared United Wa State Army, few outsiders have visited the remote region, home to 600,000 people and officially known as “Special Region 2”.

Kyaw Thu Latt and his colleagues left immediately. It was a rough trip. The monsoon was in full swing and the infrastructure was poor.

“The car was for (medicine) and the humans were there to push the car,” he said.

They rode donkeys or horses to reach remote villages.

“We couldn’t rest when we got to a village. We would sit down and treat patients immediately,” he said.

Communication was a challenge in villages where only the Wa language was spoken.

“I had to speak Burmese, and someone would translate that to Shan, and that would be translated into Lahu and then to Wa,” Kyaw Thu Latt said.

At one point the group made it all the way to the Chinese border and made contact with people on the other side.

“They came to welcome us, including their doctors. We are doctors too but we were filthy and completely unpresentable. It was so embarrassing,” he laughed at the memory.

This was not the life Kyaw Thu Latt had envisioned for himself.

The young Kyaw Thu Latt, who was one of only a handful of students in the area to pass his 10th Grade exams, saw a well-regarded medical career as a means to transcend his humble background.

“(I saw) that people respect doctors when their patients get better. So I thought doctors get to live a life of prestige and I wanted to live like that’” he said.

As soon as he graduated from medical school, however, life took a different turn.

Bilin was considered a “black zone” at the time because of frequent clashes between the Myanmar army and Karen rebels.

He received a plea for help from the abbot of a Buddhist monastery in an isolated village in the area. The monk, a friend of his father, was worried about the health of the villagers who were extremely poor and vulnerable to outbreaks of malaria.

“It was still scary when I graduated from medical college. There were bombings and fires. People were afraid of Bilin and because it was a black zone, there weren’t doctors. So people tended to die from malaria."

“It was supposed to be temporary, but I ended up working there for eight years,” he said, adding that the area has been peaceful for about a decade.

Kyaw Thu Latt then joined the civil service and was promptly sent to Shan State where he met his wife and continued his adventurers, including his Wa trip.

The harsh living conditions left him with health problems of his own, however, and he retired from the civil service.

In 2003, he joined Population Services International, a health group that has operated in Myanmar since 1995, working with some of the poorest and most marginalised people in Bilin -- those suffering from communicable diseases.

Malaria used to be the most common illness in the area, mainly affecting workers engaged in backbreaking work in the gold mines outside the town, Kyaw Thu Latt said. The mines are now exhausted and malaria is also petering out.

The new menace, according to the doctor, is tuberculosis, especially in children who have weaker immune systems.

“At first I was reluctant to treat TB patients, because my own health is not so good. I was worried about getting infected too. But to see a patient recovering really gives me joy and I want to keep doing it,” he said.

“If your body has a good immune system, you can withstand the disease. But poor people can’t afford really nutritious food. Also they tend to have to interact with a lot of people. For example, say, a vendor at the market has TB. He or she has to keep working for his or her survival. When you cough, when you speak, the virus is spreading. From there, it’s easy to pass it to the kids.”

The job can be thankless.

“The people in Bilin… don’t value themselves. You have to take (tuberculosis) medicine for six months but they stop taking it as soon as they feel better,” he said, explaining that those who cease treatment early can become drug resistant.

Kyaw Thu Latt relies on a network of around two dozen volunteers to cajole patients into visiting him regularly.

“We have to take their mobile phone numbers and send my assistants on motorbike (to track them down).”

Myanmar’s threadbare healthcare infrastructure adds extra barriers.

TB come patients need a chest X-ray and while Bilin hospital has a machine, Kyaw Thu Latt said the operator died a year before and had not been replaced. Even if they travel to hospitals further afield patients are often confronted with power cuts that render the machines useless. They rarely schedule a repeat visit.

For all the challenges, Kyaw Thu Latt is not considering cutting back on his seven-day-a-week clinic schedule any time soon.

“When the children first arrive, they are skin and bones and quiet. The next time you see them and they’re well and playful.”