Kamella Lama smiles warmly, radiating a gentle patience developed during decades in schoolrooms, as she weighs the knife in her hands.

It is a silver dagger, heavy and ornate with the cold curve of an ivory handle and a gleaming scabbard etched with delicate designs and lined with blood red cloth. Flowers and vines envelop its flanks and a butterfly is etched in the centre, captured wings spread, as if mid-flight.

This is the only traditional Gurkha dagger in this area of Pyin Oo Lwin and an important link with cultural heritage for a community whose ancestors travelled from Nepal to serve as soldiers in the British colonial army in the 1800s.

“It’s called Khukuri. It dates back to my grandfather’s time. He gave it to my father,” says Kamella.

The retired teacher never married, but almost every local wedding ceremony features her precious heirloom.

“Whenever there is a Gurkha wedding here, people come and borrow it from me because the groom has to wear it,” she says.

“Some people turned up a while ago wanting to buy it. They wanted to pay in dollars. But I won’t sell it.”

Pyin Oo Lwin, a temperate hill station some 40 miles from Mandalay, has long been synonymous with the Nepali community, many of whom descended from the 10th Gurkha Rifles which was stationed in the town from the 1890s.

“My father was briefly in the British Army and his brothers-in-law were all in the army.

“My grandparents came from Nepal. The rest of us were born here,” Kamella says.

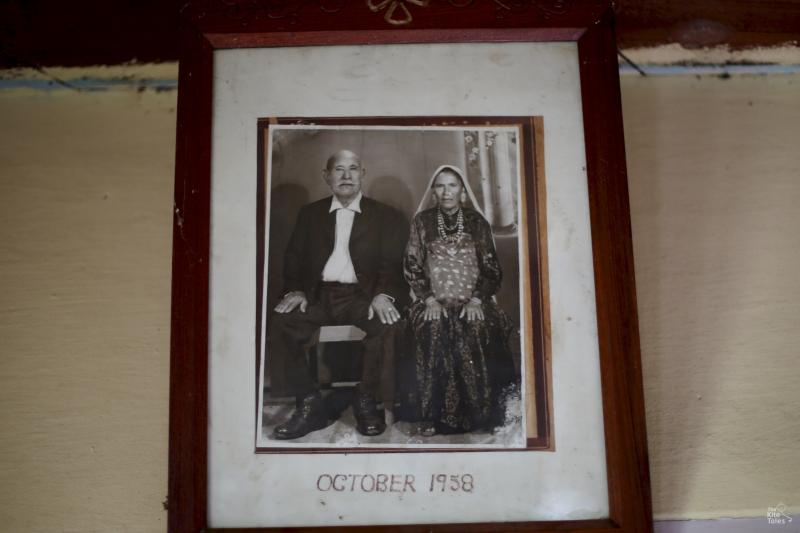

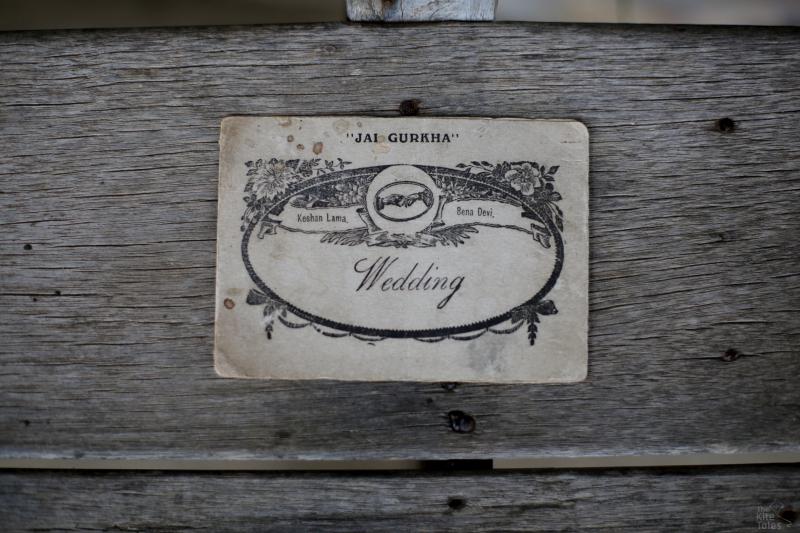

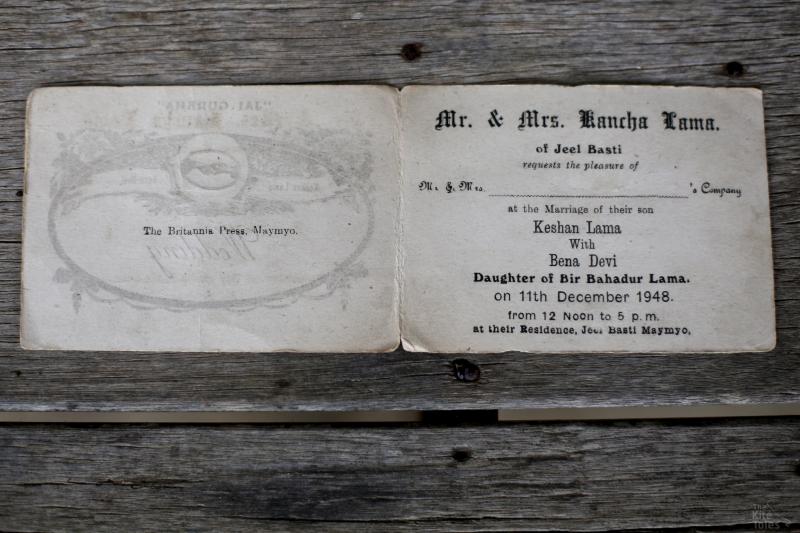

She pulls out another precious family artefact. It is a small scrap of paper, inscribed with a careful type announcing the wedding of Keshan Lama to Bena Devi -- her parents -- on a December afternoon in 1948.

“There were 11 of us kids. So many! We were all born in this village. It used to be called Jeel Basti village, and the majority of inhabitants were Gurkhas.

“The houses were more like thatched huts then and there wasn’t much development, but now you see more social and economic changes.

“People are also more knowledgeable and they send their children to school. Previously in our Gurkha community, people didn’t prioritise education.”

But her family was different.

“My father had a big lorry and he brought goods from Maymyo ( the former name for Pyin Oo Lwin) to Mandalay. He would go to village after village -- where later I would later work as a teacher -- and pick up corn, flour, peanuts, ginger, seasonal crops, and then go to Mandalay.

“That’s how he paid for our education. He was able to earn a decent income so (the girls) were sent to St. Joseph, an all-girls school. The boys went to St. Albert.”

It is a time she look back on with fond memories. But the education system began to deteriorate after a coup brought in Ne Win’s military government in the 1960s, which stripped foreign influence and banned ethnic minority languages from the classroom. Classroom sizes grew too, from around 20 to 30 students per class to 70, putting pressure on teachers like Kamella.

“They were Christian missionary schools until 1962 -- our 2nd grade -- when the schools were nationalised. They all became government schools. But until we finished our 10th Grade, it was still a girls-only school.

“(Maymyo) became a boarding school town and that swelled the student numbers. All the kids from other towns and Shan State came here to study.”

Despite the pressures on the education system, Kamella decided to devote her life to teaching, eschewing the family gene for trade.

“I’d always been quite bossy since I was young. Even with friends, I wanted to lead. So when I finished 10th Grade, I thought I should be a teacher.”

If you drive a few minutes from her home, through narrow village streets and then up an innocuous country track is the tranquil Tibetan Mahayana temple, with its fluttering coloured prayer flags.

She says it was initially a struggle to bring modern ideas to the community.

“There were lots of difficulties. Parents in the Lama clan aren’t very educated and are quite traditional. But we worked really hard and now things are much better.

“We did things like arranging award ceremonies for the Lama clan children who passed 10th Grade as a way of encouraging children to study. It was only after I arrived at the Gumba that they started holding these ceremonies.”

While she never had children of her own, Kamella’s teaching career gave her a pivotal role in the lives of many underprivileged kids.

“My first posting was in 1977 to Hoko village in Shan State.

“There was a Shan ethnic Danu child, the son of a widow who sold fried snacks. He was smart and even won an award in 4th grade for the whole township. But his mother could no longer send him to school, so I adopted him and sent him here to continue his studies. He passed 10th grade with a distinction in history,” she says proudly.

“He joined the army and became a captain. He’s now married with children, and even grandchildren. He’s now back in Hoko working and he comes to the house with his family now and then to pay his respects.

“I didn’t do it because I wanted something in return. I just wanted him to have a good life. But I was thrilled when he came here.

“I used to donate education this way. I would teach the students here or send them to boarding schools.

“Just recently, a student came back from the United States and came to see me. He’s now married with two kids. He said, ‘I’ll never forget your kindness’.

“I feel really sad when I see young children who can’t go to school. If they aren’t educated, their lives can stagnate at such a young age.

“If you aren’t educated, it’s like you’re blind. That’s why I teach people for free. I think of these children as my children. That gives me joy.”

Interviewed October 2016