It’s a typical car-horn blare morning in Yangon and the air is quickly thickening with heat and dust and the impatience of the day. The city sounds fly around Athong Makury’s sparse apartment, never quite settling, as the energetic president of the Council of Naga Affairs talks passionately about culture, language and the many injustices that have been inflicted on his proud homeland.

While he seems at ease in the chaotic, clustered streets of this diverse neighbourhood, his heart is high in the mountains, in a frontier region so remote that few outsiders make the journey.

The Naga hills are home to dozens of distinct tribes, many with their own languages, along both sides of the India-Myanmar border. In Myanmar, they fell victim to decades of neglect under a military government that saw ethnic minority border regions as unruly backwaters to be controlled, not cultivated. Infrastructure is so poor that to travel between the main towns you either have to go on foot for days or leave the region by car and re-enter at another point, sometimes by boat.

This isolation has suspended Myanmar's Naga areas in many people’s imaginations in their fearsome head-hunting past, giving them a romantic, wild reputation that ignores the urgent questions of the present.

An eloquent advocate for his people, Athong is among Myanmar’s most incisive voices on the challenges facing ethnic people.

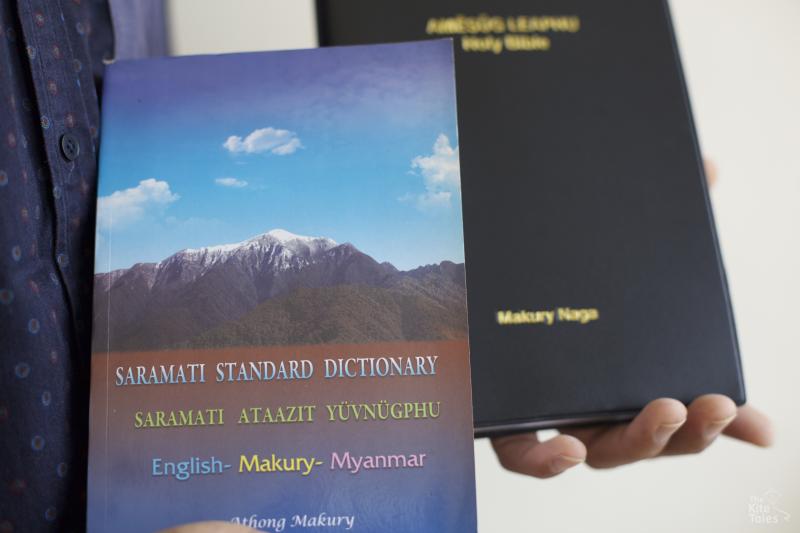

Descended from chiefs of his Makury tribe -- some 50,000 people on both sides of the border -- he grew up in the Myanmar town of Layshi and crossed the frontier when he was a teenager for education in India's Nagaland. While there he began work on the first comprehensive dictionary translating his native Makury language to English and Burmese.

He has even adopted Makury as his surname.

“Actually there’s a name in between -- Athong Mongtsüglë -- that is peacemaker and also tax collector. We are given tax for making peace," he explains.

"We have at least three names. One name is kind of your official name, the other is a kind of nickname and the other one is the name by which people call you in a mockery sense. It is given based on one’s character. And in my community they don’t want to say Athong Makury, they would say Athong. So there could be many Athongs. Which Athong? Athong Leayeipu: the one who writes a lot. The one who writes funny things actually.”

The myriad Naga tribes have struggled to maintain their traditions as the influence of outsiders spread, bringing Christianity and new languages. Their homeland came under foreign control when the British ventured up into the mountains from their Indian tea estates in Assam in the 1830s. When the colonial regime retreated after World War II the region was severed by a new frontier between India and what was then Burma, eventually creating Nagaland in the former and more recently the Naga Special Administrative Zone in the latter.

Though problems remain on both sides of the frontier, Indian Nagaland is a relatively developed region, with an active political scene. But on the Myanmar side, access to education, healthcare and jobs is far below the national average, and people lived under the shadow of the brutal military regime for generations.

“I feel I am very different from my fellow friends who were brought up in Burma and sometimes I feel that I have over-confidence,” says Athong, explaining the "heaven and earth difference” in opportunities for those raised on either side of the border.

“When I observe my fellow friends (who think) ‘oh if I use these words what will happen?’ — so much with fear — I really feel pissed off. But I feel very free to speak and I feel very free to argue and debate, because that is already a culture for us on the other side.”

Athong, who started working on his dictionary when he was still a student in 2008, says his research gave him a deeper understanding of his own culture.

“And the more I know about my culture, the more it helps me to respect others. I used to think ours is a very poor language but the more I dig, the more I find. So I feel every language is beautiful and it has its own uniqueness.”

He visited Makury villages across the remote region, collecting information and negotiating the delicate task of making sure the dictionary was inclusive and accepted as the official format.

“Each village wanted to make sure that their (version of a word) was included. It was really good to meet elders who can really give a clear guide, who can explain some of the folklores, how they are told, how they are understood or interpreted.”

Translating certain words or phrases into English and Burmese was another major challenge.

“Like especially (to hit) with the knife or machete. In Burmese we have got around five to ten words like khote tae, chaing tae, thet tae, like very few, but in Makury, many. For example pei, tu, dzeng, sat.”

The plethora of vocabulary linked to violence may reflect the region’s warrior past, he acknowledges, but it is also useful for clarity.

“The main point is how they use language and how the vocabulary is used to convey the meaning, express how they feel and what they think,” he says.

The Makury language was first formally written down in around 1960, but it had been given a written form before — by students in the missionary schools that were set up across Nagaland in the 1800s.

“They started writing their mother tongue for communication among themselves - that’s how our Makury (written) language came into being, that’s how it started.

“Roman script is really good for spelling Naga languages. If we write Makury with the Burmese script it’s really difficult. Even my name."

Children in Myanmar’s ethnic minority regions are taught only in Burmese — a controversial policy that many feel leaves them disadvantaged.

“My concern is Naga people, we are never competent in school education because we are not taught in a language we know.

“Some people might say, ‘oh it’s because you guys don’t try hard, that’s why you can’t compete’. That’s why you don’t become doctors, you don’t become engineers, you don’t become researchers you don’t become x, y, z.

“The majority of people are not like me. There are many people who struggle a lot to speak Burmese words. And also there are many people, many kids going to the schools who don’t really know what Burmese culture is, even though they are speaking Burmese.

“Even in terms of teaching materials, the environment, all these matter for a person to become successful in education. The curriculum itself -- “ya, yathar..” -- is a rhyme in Burmese. It says riding on a train happily, that kind of thing. But people over there don’t know what a train is, they haven’t seen.

"And that’s how people are losing. That really frustrates ethnic peoples.”

School history has also traditionally been skewed towards the majority Bamar.

“What we learned in our past is, for example, Naga people are subservient. We are the people who always had to pay tax to Burmese kings. It’s wrong history. They think they are the boss and the other guys are lower than them, that kind of attitude. That really destroys the relationship between the Burmese and the ethnic people. And also an understanding of our culture, respecting one another’s culture. This is really important if we want to build a good relationship between us.

“Those who want to keep the Nagas always under, they say ‘Oh they are always divided and they have no unity’, because they fail to understand Naga villages are independent villages, not subservient to one another," he says.

Athong, whose father and grandfather both served as chiefs, adds that the Makury system of rule has its own democratic merits, with village councils approving the appointment of leaders.

Most ethnic minority areas have long been administered by civil servants largely drawn from the Bamar majority. But there is a perception that they are often reluctant visitors to the remote and rugged border areas, with their poor infrastructure and different cultures.

“Mostly those government staff (are) sent to ethnic regions because of disobedience, so before they are sent they are already frustrated," says Athong, explaining that local people see these newcomers as representatives of the Bamar.

“The type of Burmese they see over there is really scary — (the people) they come across are mostly from the administration, from military. So they think that these are the Burmese. So they don’t want to send their kids to the Burmese area (for school)."

After the Naga areas were cleaved in two at the end of World War II, insurgencies began to build on both sides of the border. While the fighting in Myanmar stopped decades ago, deep resentments remain. And so do the Burmese soldiers.

“I think we haven’t changed our mindset even though we have come more than 60 years. Because they feel that the solution that comes through the barrel of a gun will last, but to me it will never last. Because (the solution) is only through negotiation and mutual respect and understanding.

“We are the ones who gave birth to many insurgent groups in India, even on the Burma side. And realising the futility of violence — we have suffered more than 500,000 people in this conflict. It is too expensive. It’s too costly for us. We are also very much from a warrior culture. I think in the world we are the worst head hunters, so we have come from that and realised the futility of violence. I really condemn any form of violence.

“In this postmodern world everybody knows what to do, you know. I mean the what. But we fail to see the how. How it should be done, how we can achieve it. This is really important,” he says, adding that while a recent rule change has opened up space for ethnic languages to be taught in schools after decades of prohibition, there are no funds to make it happen.

“We talk about peace, we talk about reconciliation, but I think this is something really important to look at these aspects. And language is one of the things. Because ethnic peoples have no privilege to learn.

“Language is the heart of culture. And culture is the heart of society.”

Interviewed October 2016