Pascal Khoo Thwe’s ancestral home has sunbursts carved on the balconies and umbilical cords buried in the garden, neat dry curls of new life preserved in honour of every child born in the old kitchen.

The original structure, gnarled by age and gnashed by marauding termites, was built over a century ago. It has been augmented with newer buildings, sprouting over time like new branches on an ancient tree.

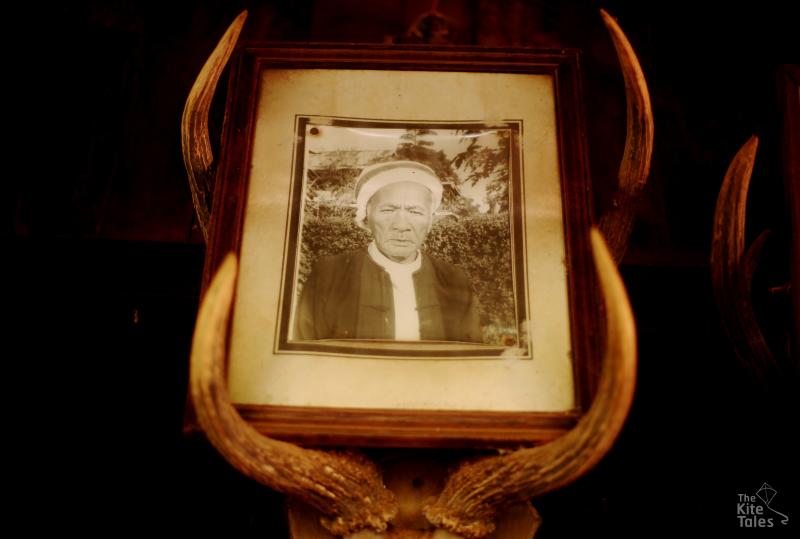

Family life is focused in the main house, a rambling elegant structure built in 1945 by Pascal’s grandfather out of the ashes of the Second World War. Its walls are tar-blackened to protect the wood and festooned with the fragments of several lifetimes: Sepia family portraits are mounted on deer antlers, posters of Jesus are in pious proliferation, and old toys recommissioned as protective spirits peer down from the rafters. “1972 Elvis died” is scrawled in a chalked tally of memorable dates on one wall, though this was maybe a premonition since the King actually died five years later.

The upper floor veranda is thrown open to the afternoon breeze, which threads its way over the town from the rippling tides of the vast Mobye lake. In the garden two pigs with dictators’ names snuffle contentedly in their pen, while rare local orchids hang among foreign guests — fig trees and a spreading grape vine.

An ethnic Kayan, Pascal spent his childhood roaming the countryside around this house in Pekon, southern Shan State, at a time when the old traditions still wove people and nature together.

There are so many amazing stories of lives tossed into the maelstrom of Myanmar’s long struggle with military rule, but Pascal’s must rank among the most extraordinary. His autobiography “From The Land of Green Ghosts” is a vivid journey from the almost mystical forests of his youth to his studies at Mandalay university, where he was swept into the tragedy and violence of Myanmar’s 1988 student-led uprising. In the turbulence he fled to the jungle and took up arms against the military regime. But a chance encounter with a British professor — and his love of James Joyce — gave him the chance to study at Cambridge University. He has described his transition from tribesman to author as going from hunting animals to hunting words and stringing them up.

Pascal returned to Myanmar for the first time in 2013. He had been away for a quarter of a century.

“It’s funny because I dreamt, literally dreamt, the home coming. And it’s exactly like what I dreamt. It’s very bizarre but I was prepared emotionally.

“The house was in a mess, everything in a mess. This veranda was crumbling so I replaced it as soon as I got back. So repairing the old house is also a symbol of repairing or rebuilding the community.

“(My family) are very happy but also worried. They are worried about the local authorities’ reaction. Maybe they are a bit worried I might despair, give up and go back to the West.

“I’ve not even had time to think about it. Basically I can survive as long as I can do something here.”

After Pascal’s father died in the mid 90s the family lost the motivation to preserve the house. Now he has returned and is working on a sustainable tourism plan for the region with the UN’s International Trade Council.

“There was no one organising because there was no family head. I had to come back myself.

“It’s a delicate balance, I want it to be more genuine but I don’t want to make it into a situation where people living in the house feel they are showpieces. It should be much more like a living museum, but one where the items sometimes go away and come back. So I want to make them aware that it is an important place for the history of our clan, our tribe.

“This is the genuine birthplace of all the children, where all the ten brothers and sisters were born,” he said, explaining that while there were no painkillers, women used traditional ways to ease the agony of labour.

“Whenever the children were born my mother came to stay in the kitchen. There was a fire and there used to be clay pots and my father would place a stone (in the fire) until it turned red, and put it in the clay pot and then my mother would sit on it.

“When the baby is born, you cut the umbilical cord, dry it and bury it.

“I remember big snakes. I think we still have one in the house; we keep it as a guardian spirit, it’s hiding somewhere near the pigsty. The other snakes are mostly on that tree, the green ones. They wait for the birds."

At the entrance to the main house there is a narrow gap, you could get through it only if you lay flat on your belly and posted yourself in like a parcel through a letterbox. It is the bomb shelter and just to look at it makes you want to gulp air into your lungs.

“It’s very small. I remember there was the civil war and when there was shooting we used to go in there. I think it must have been the late 60s, when I was two or three.”

“I am trying to save the old works of my father and grandfather.

“This is my grandfather’s musket, British made. It has a really interesting history.

“Nearly 200 years old, this gun. First or Second Anglo Burmese war and they were still using it by the Second World War. So when war broke out the British trained some of the tribesmen. They didn’t give them machine guns they gave them these flintlock muskets.

“He marked all the Japanese he shot here (as faint notches on the gun barrel). I am sure about 20 Japanese.

“The gun shape is originally for a Westerner; for average Asiatic people it’s a bit too long.

“The Japanese were using rifles so you can (mimes mechanism for firing in quick succession). This one you had to put the gun powder in, it takes at least two minutes. You kill one, you run away, you wait for another one to come and shoot. It’s mad isn’t it?

“Later my grandfather just used it for hunting. The animals (displayed on the walls of the family home) got killed by this gun.

“(When I was fighting in the jungle) I would use an M-16, the automatic machine, they are shorter of course and also they fire rapidly. But they are less accurate.

(Would he have cut any notches in his gun?) “Probably not.”

Pascal says his grandfather was "like what he looks; very fierce. Quiet and fierce".

His great grandmother — an early convert to Christianity — came to the area with a group of Italian missionaries, who were set a challenge by the ruler of Mobye to determine how much land they would get.

“The king gave them the hide of a cow and said ‘You just cut the hide into strings, tie them together and line them up and you can take as much land as one hide’. They got about 20 acres.

“The Italians brought avocados. Pasta, salami and also they brought fagioli, the pinkish beans. They brought potatoes, soursop — custard apples — coffee too.

“The tribes normally tend to live on top of mountains so sometimes they come down to the plains to reclaim their land. So that’s how it happened. It was only about 10 families I think when they started (the Pekon settlement).

“People used to bring chicken and pigs when they came to stay with you. In the old days money was not the main thing so you bring your vegetables and the like. And you say ‘oh I need to stay in town for a couple of days, I need to go to the hospital’.

“I want to revive the old tradition, how the community leaders used to work.”

Pascal is thoughtful, preoccupied by the many dimensions of the challenges ahead, but he also has a steely streak. He laughs often, with a gappy grin these days after his young son knocked his two front teeth out.

“There are still some local leaders not very keen on me helping the people. But I don’t care, I am only giving them advice when they ask me about literature, culture and society,” he says.

“When we work for the village, community based tourism, it’s all about their community, cooperation, traditions and you have to be aware of that if you really want to sustain something. You can do business just to make money but it doesn’t help the local people.”

Interviewed May 2016