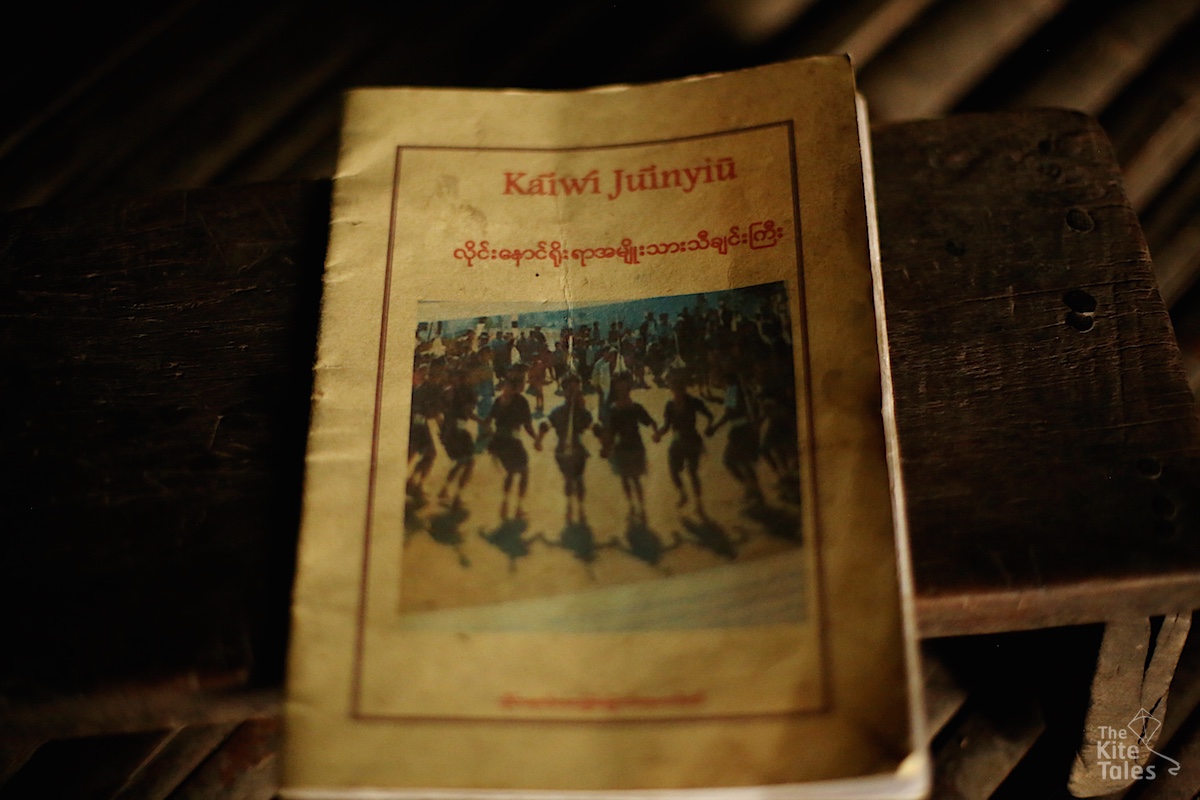

Every year the Naga Lainong tribe holds jubilant traditional Kaīvi New Year festivities in local communities. Everyone gets involved, feasting or holding hands and dancing to the sacred festival songs, which whirl through the celebrations as day turns to night. The lyrics are stories that coil and unspool. They are the legends of Ga, the creator, legends of the fish, the sun and the moon. And they are also tales of local life, of war. They are mirror songs that can be sung back-to-front, front-to-back. Ngòm Pok leads the song and no one can stop dancing until it is finished.

The Naga believe that these songs are a hallowed inheritance from Ga and have passed them down diligently from generation to generation. Ngòm Pok’s family has overseen the festival song for decades. The 78-year-old is now teaching his own son the ancient Lainong traditions in the hope that they will survive to be handed on to future generations.

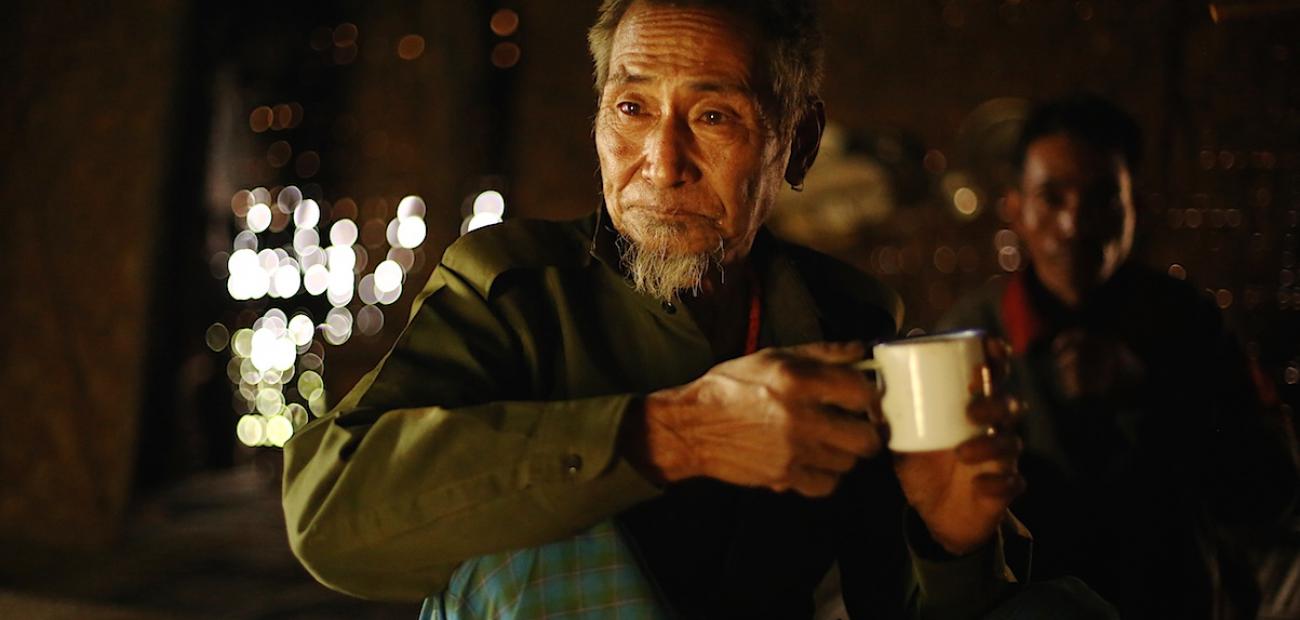

“There are the songs you can sing at normal times and the traditional songs. The type that’s sung at the Kaīvi festival can only be sung after offerings have been made to the spirits, like it has always been since the old days. And once you start you have to sing until day break,” said Ngòm Pok over tea in his family home.

“(During the festival) we instruct the singers when to change the song and what lyrics to change to.

“The village elders asked my family to do this duty because only we knew this song.

“My father taught me the lyrics very carefully. When my big brother was around, the honour of leading the song was his. I took over after my brother passed away, so I have been doing it for about 10 years.

“The traditional song has now been documented on paper. I helped with that, but someone else wrote it down.

“I am teaching one of my sons the song. He’s about 35 years old.

“The whole Lainong tribe should be concerned about losing these traditions. I can’t worry about this alone. Everyone has to support me and take part in preserving these traditions.

“I have tattoos of Naga heroes on my chest. A long time ago when there were fights between villages, if you killed someone then you would have a figure of a man tattooed onto you. That was the idea, but these (wars) haven’t happened in my lifetime.

“(This belt) would usually be worn at traditional celebrations like the New Year festival. It is only worn by men. I don’t wear it though, not even at the festivals. I bought it for my son.

“We call these haihu. There’s a place where you can put your knife. This is goat’s hair for aesthetics. These are shells.

“Previously, when it wasn’t so peaceful, every tribe would include pictures of Naga heroes.

“I got it quite a long time ago and paid about 160,000 kyats for it. Someone from another village came to sell it so I bought it. People rarely sell such ornaments, it’s only when they are facing difficulty that they would part from them.”

“I was born in the old village a little higher than we are now but I grew up here.

“Lahe has changed a lot. There are more people living here and the mountains and forests have changed too. Of course there’s more development.

“I weave in the mornings and evenings and go to my farm during the day.

“Pretty much everything in my house I wove myself, including special baskets to carry firewood and rice, to catch fish and to sift rice grains.

“I started weaving baskets when I was young. My father and brother could weave too.

“It takes about a week to make each piece because it’s not the only thing I do.

“If I’ve made two or three baskets, I sell the extras to those who cannot weave. Not many people know this skill anymore. There are some villages with very good weavers, but they are about two hours from here. If they don’t come here, there aren’t any other places to buy baskets.

“I’ll keep doing it as long as my eyesight is good and my son can split the bamboo into strips for me. I still don’t wear glasses.”

Interviewed April 2016