Philip D’Silva carefully spells out the unusual name he inherited from a Portuguese seafaring great-grandfather. But few people in his native Myeik, on Myanmar’s tropical southern coast, know the jovial former school teacher by his European alias.

“Here they know me as Tin Tun Aung. Only my close friends know me as Philip,” said the 71-year-old, leaning back on his chair and into a shaft of brilliant winter sunlight.

With a Christian mother, Buddhist father and Muslim wife, Philip D’Silva’s family is a happy tangle of many of the rich threads that weave through modern Myanmar.

“It’s no problem. We have an understanding with each other. They try to help me doing my religious rites and I don’t say anything about them doing their religious rites,” said D’Silva, a Catholic Christian, in the English he learned at missionary school.

He jokes that the D’Silva family’s mastery of interfaith harmony could provide a useful blueprint for his Buddhist-majority country, which has grappled with deteriorating religious relations in recent years.

“I don’t find any difficulty. Now even the government is trying to (create a) group of leaders from the different religions, I think I should be there as a consultant!”

Myanmar’s former military rulers plunged the country into isolation and would routinely stir xenophobic suspicions, trying to ossify a narrative of a nation at risk of “foreign” interference. But D’Silva shrugged off those prejudices.

“This is our native town, I was born here. I didn’t feel like a foreigner because I was born and brought up and live (here). Also I am a Burmese spirit. I love people here. Only the rulers I don’t like,” he said.

Portuguese seafarers, mercenaries and spice merchants began to land in Myanmar in the early 1500s, as they fanned out across the region following the conquest of Goa in India and the lucrative trading shipping lanes through the Malacca Strait.

Many took work as soldiers for hire for the kings of what is now Burma, from the ancient Bamar kingdoms of Pegu and Taungoo in the central regions, to Arakan in the west*. While these fighters became key figures at the often multi-cultural courts, their countrymen also introduced Catholicism.

D’Silva never met his great-grandfather and struggles to extrapolate history from legend. His Portuguese ancestor may have bequeathed his religion, but the details of his story dissipated in the family bloodlines.

“They came by sea I think. Probably they came around sailing and they arrived by accident. Spanish and Portuguese were said to be great sailors according to our history,” he said.

He longs to find an anchor to tether himself to this history.

With the end of Myanmar’s isolation, more foreigners have begun travelling to Myeik and D’Silva asks those he comes across if they know any Portuguese people who share his name.

“I try to ask some who came here if they have any D’Silva friends, if they have I would just like to get some contact with my ancestors, (even though) they won’t know me and I don’t know them,” he said.

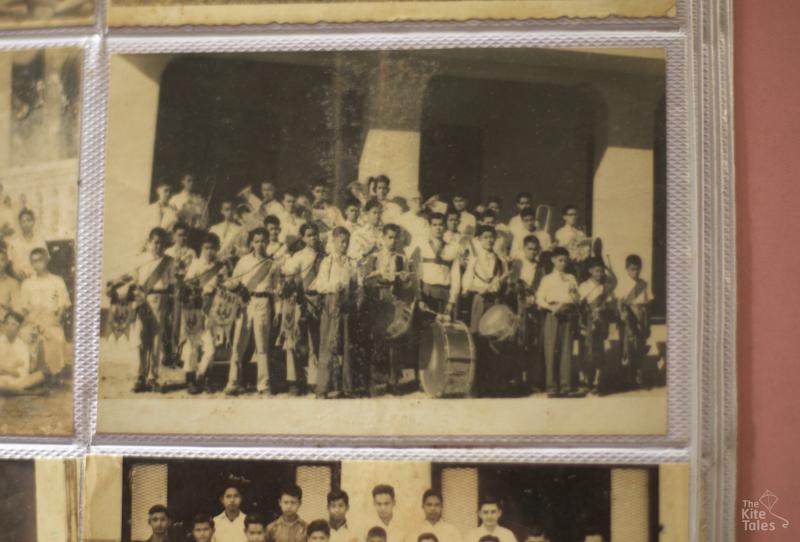

He barely spent time with his own parents, who sent him to St Patrick’s Catholic boarding school in the town of Mawlamyine at the age of six.

“We were allowed to return home only once a year,” said D’Silva, whose parents scraped together the money for his education from his father’s pay as a medical compounder.

At first he found the wrench from his family deeply traumatic.

“We used to cry before going to bed. We longed for our mothers. Kids of my age, we grouped together and cried for about one month. After that we became used to it.

“In boarding school we were like brothers, even now when we meet one another we are like brothers. We didn’t get into much trouble during our childhood days. Sometimes as kids we may find some quarrel with each other, we may fight. But after fighting, apart from our boarding group we had no one to talk to, so we became friends again. We fight today, we became friends tomorrow. Just like a family.”

He even adapted to the strict routine. So much so that more than six decades later it unspools from his memory without hesitation: “5.30 am. Sometimes on the rainy days it’s very difficult to get up. But we have to get up, bathe and go to church — the church was just beside our boarding school — and breakfast, then we have to go to school. After that we have to play about one hour in the daytime and study one hour. And evening we played for two hours, bathe at 5.30 and we study from 6 to 7pm. Seven we have dinner, 7.30 we play for around half an hour; 8pm we have to go to bed.”

He had hoped to become a doctor, but Myanmar’s rigid higher education system thrust him towards zoology. He moved home to Myeik after graduating to be closer to his mother, by then a widow, and took a job in the local school teaching English and biology.

All Myanmar’s schools were nationalised by the military government in the early 1960s and standards were beginning to slip as resources became ever scarcer.

But he drew encouragement from the missionary teachers of his own childhood.

“I am inspired by all the brothers. They are good and strict and straightforward. I liked them. Although some students don’t like to be well disciplined, I like strict discipline teachers. Up till now I don’t smoke thanks to the brothers.

“I liked to help train the students. If they find success in life, I am happy. Most of my students are now doctors, high officials, sometimes they come and see me and chat about the good old days,” he said.

When he was reassigned to a school in another part of the country he retired and became a private tutor in order to stay close to his family.

He and his wife, an advocate, had nine children and D’Silva is unfazed that many of them followed their mother’s Muslim faith.

Far more important, he said, is that they adhere to the exacting behavioural standards of the brothers at St. Patrick’s.

“I want them always to be good and studious, hardworking and to be sincere about everything,” he said.

* For more stories of the Portuguese influence and Myanmar history in general, also see Thant Myint-U’s “The River of Lost Footsteps”

Interviewed November 2016