It was early on December 5, 1974 and the sadness that hung like morning mist over the Kyaikkasan sports ground was stirred with a restless disquiet. Crowds of mourners clutching floral wreaths had gathered to pay respects to former Myanmar United Nations Secretary-General U Thant, who had died recently in New York.

His body had been taken to the old racecourse for this public ceremony by Myanmar’s military government, led by strongman Ne Win, which had announced plans for a burial at Kyandaw Cemetery later that day. But the enraged university students thronging into the stadium believed anything less than a state funeral was an insult to U Thant, who had garnered global respect for his skillful handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis during his time at the helm of the UN.

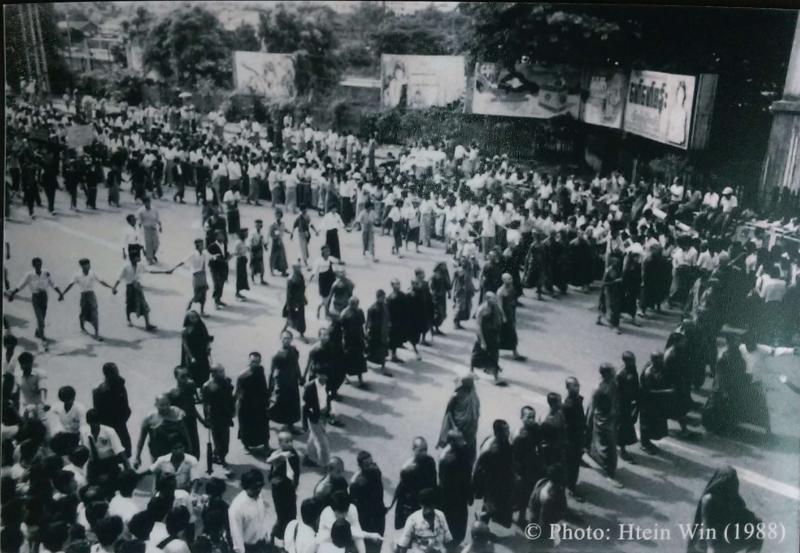

Just before the body was due to be taken to the cemetery, the students seized the casket and carried it to Yangon University, with the help of monks and ordinary people. A stand-off with the military regime lasted a week and ended when soldiers charged the hall where the body was being held. And unverified number of students were killed in the bloodbath.

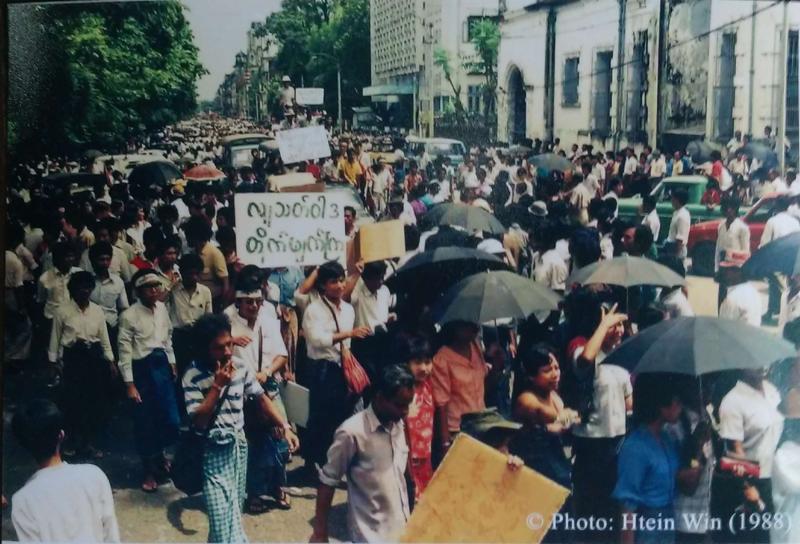

For Htein Win this painful episode in Myanmar’s history was also a key moment of transition, as his passion for taking pictures became his life’s work. A medical school dropout, he shrugged off his failure to become a doctor — a lucrative and highly respected profession in Myanmar — and chose financial uncertainty and even to risk his freedom by becoming a photographer. Through his lens he would witness the mass protests and bloody crackdowns of 1988 and the 2007 monk-led Saffron Revolution.

“I decided to make a living as a photographer after failing my medical exam for the third time in September 1974. Then in December we heard UN Secretary-general U Thant had passed away and there would be a funeral. The university students were dissatisfied with the government’s plans, so on December 5 I followed them to Kyaikkasan Racecourse to document the event.

“As they brought U Thant’s body back to Yangon University, I asked permission from the student leaders to take pictures as historical evidence. But there were so many students and people weren’t familiar with each other my request was denied.

“Luckily, one of my teachers lived inside the university compound, so I took photographs from his home.

“But I wasn’t there when they stormed the compound. My teacher took those photos. His wife had told me to leave the night before. She said ‘If you don’t, I’ll kick you out.’ They probably guessed the army was going to crack down on the students.

“Many historical events happened (in downtown Yangon). The 1988 protests happened here. I took many photos then.

“I was detained in December 1988 for four weeks for trying to take photos of the army. After my detention I went to collect some negatives from friends who had been looking after them for me. But they no longer had them.

“They burned them after hearing there would be a house search.

“I was detained again in 1989 for 11 days. No reasons were given.

“In 1990, a foreign friend said my photos should be in an archive. I didn’t have any contacts so I asked them for help and we sent the remaining pictures. I got lucky.”

Over 500 pictures are now held at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam.

“The photographs that are most precious to me are images of historical events.

“The others that are important are portrait shots of artists. I was inspired by Sayar Paw Oo Thet (a well know modern Myanmar painter), who showed me a book by Yousuf Karsh with portraits of Churchill and Audrey Hepburn. I’ve been taking these portraits for over 40 years and I now have almost 200 shots.”

“I learnt how to use a camera when I was 6 or 7. My father, an amateur photographer, had a Rolleicord and would get me to press the shutter button to take his pictures."

Htein Win had a missionary school education until the age of 11, when his parents sent him to Darjeeling to continue his studies.

“My father gave me a camera to take with me. But I had to come home after the coup by Ne Win in 1962.

“I ended up at the Institute of Medicine because I had high marks and U Ne Win did not allow us to study English undergraduate degrees. I was not interested in medicine but I met three of my photography teachers there, so luckily I was able to practice taking pictures.

Under Ne Win’s socialist government, even camera film became a rarity. In those days, photographers would have to write to the trade and commerce office for permission to buy more rolls. There was also a thriving black market, centred around the photography shops that lined Yangon’s Sule and Bar streets.

“If we were allowed 10 film rolls we would sell five of them to the shops and keep five to use. It was about two kyats cheaper to buy from the government,” Htein Win said.

Photography shops are still a fixture of downtown Yangon. The tiny cluttered workshops of 33rd street are the saviours for those with broken cameras. Using everything from screwdrivers to toothbrushes, these master repairmen perform surgery on film, digital and video cameras alike.

Htein Win said he and his contemporaries “dismissed digital when it first appeared. We said film was better.

“We were wrong,” he added chuckling.

(Interviewed in June 2016)