This story is part of a series on children working in the teashops of Mandalay. We also spoke to a boy working in one of the teashops and his employer

For the teashop kids of Mandalay, childhood is squeezed into the cracks of each care-worn day: football on the street between shifts or snatched minutes calling parents in the half-forgotten village where they were born. For some it is also in a classroom.

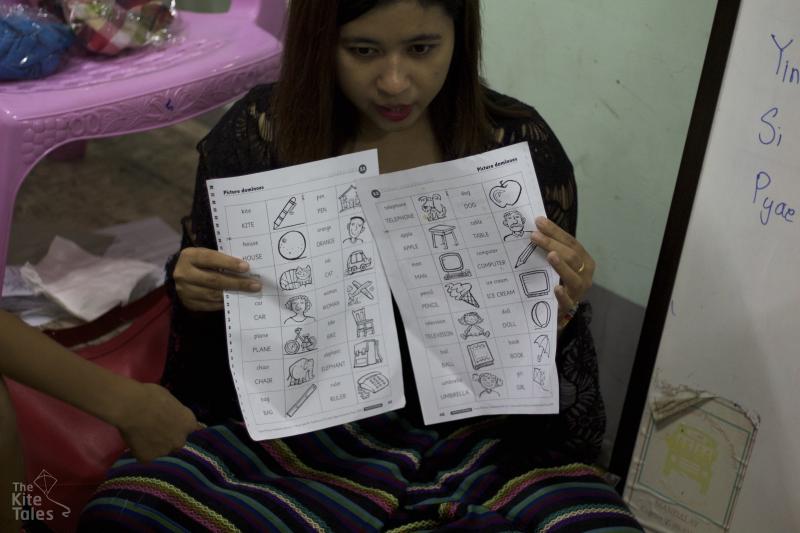

In a schoolroom appropriated from the storeroom of a clanking, raucous teashop, Ei Mon Zin teaches a tight huddle of kids. Her lessons prioritise useful skills — maths, basic hygiene, and English language to help them speak to tourists and maybe land a better paying job. She is a volunteer teacher with the MyME education project, which provides free classes to child labourers. Over 10% of 10-14s in Myanmar are economically active. Often forced into work by poverty, they support their families by toiling on farms, hauling rocks to build roads, or moving alone to the cities and working in teashops and construction sites. They are transient and sometimes a promising student will leave their job and vanish.

Ei Mon Zin’s own childhood was marked by a sudden deterioration in the family fortunes leading them to seek sanctuary at Mandalay’s Phaung Daw Oo Monastery, a Buddhist compound with a school for poor children, where she now also works. At 25 she is still trying to work out what her own future holds. But one of the things she values most is the freedom to choose her own destiny.

“To be honest, I hadn’t thought of becoming a teacher when I was young. I wanted to become an engineer. Looking back now, it wasn’t because I really wanted to become an engineer, I just thought that if I had a good job I would have a lot of money. But when I graduated from high school I only had a normal pass — not enough to get into the engineering university. I thought if I couldn’t be an engineer, I would work on my English skills.

(She applied for a course in Chiang Mai with the Thabyay education group in 2008)

“When I got there I had to work really hard because I was the youngest. I met so many older brothers and sisters and there were many people from different ethnic groups too — Shan, Kachin, Kayin, Myanmar, Rakhine, Mon, oh lots of them. It was the first time I actually had intimate conversations with people from other ethnicities. It was a great learning experience for me.

“Then I applied for Miriam College in the Philippines. It’s a single sex college established by missionary sisters, so it is very strict. It was to be a long stay — four years and four months.

“The first year was quite dreadful. There wasn’t anyone of my age and the Myanmar community there is small. I felt like running back home.

“Also in the class they graded you on your participation. But I didn’t ask questions, I just sat quietly and read. For the first year I didn’t get good grades.

“So I changed.

“I started having Filipino friends. When you’re on your own you are more afraid and you feel small, but once you’re friendly with everyone, you can speak up without being scared. I also had to explain myself to the professors, to ask for help if I didn’t understand something.

“(In Myanmar) teachers don’t encourage children to ask questions. If a student asks a lot of questions, some teachers don’t like it. So I think the children are afraid of speaking up from an early age. You have fear embedded in you. I didn’t dare do presentations before because I couldn’t bear people’s eyes on me. But I’m not afraid of public speaking now, I’ve become bolder.

“I came home in 2014 March and I’m now working as a programme manager at Phaung Daw Oo’s pre-college programme. I also teach for MyME in the evenings four days a week.

“MyME is a mobile education programme and the students are also mobile. Most of them come from poor backgrounds and haven’t had proper schooling. But it is easy to teach most of them because they work hard and are willing to learn.

“We try and reward good students. The boys like to use gel for their hair, so I’ll buy that for them. Even if one kid is very smart, you can’t just praise him alone, you have to create ways of recognising other children. The one who never misses a class will also get an award for perfect attendance.

“There are many smart students, but they’re not always there. They’re only in Mandalay and working in these teashops to make money for their families. So there are occasions where they have to prioritise the needs of their families and can’t concentrate on school. They didn’t move to Mandalay for the education.

“When students say, 'Teacher, your lessons allowed me to do this and I’m doing well' I feel really pleased.

“There was this one boy, he was the oldest in the class but hadn’t had the opportunity to spend too much time at school. He was not a quick learner compared to the others, but he was diligent. He was really interested in English too. When his tea shop closed around 6pm, he would use his motorcycle as a taxi. This gave him extra income and he asked me to teach him directions for when he gave ride to foreigners.

“Then in April he got into an argument with the owner of the teashop. The MyME classes break up in April for the annual water festival, but when we started again he was not there. I was devastated. He would always be there even if others weren’t and that motivated me too.

“So I called him and he said: 'I’m sorry teacher but it wasn’t working so I’ve gone back to the village, but I will always remember you'.

“There are a lot of things that I value. I really treasure my parents. I’ve seen the difficulties they have gone through, so I also value education.

“Another thing that I treasure is the right to make my own decisions. It’s hard for girls in Myanmar. For example, (people think) a woman shouldn’t behave this way, should wear certain things, must speak a certain way. After I came back to Myanmar, I no longer wanted to accept this. My parents said I had changed a lot, I no longer listened to them and they questioned whether it’s because I now think so highly of myself. At first I was really upset about these conflicts. But these days, I just accept that it’s an individual’s right to decide for himself or herself. That’s what I’m going to prioritise.”

(Interviewed September 2016)