The writer is a technology entrepreneur outside of Myanmar.

Monday, Feb 1, 2021

My wife started getting seriously worried about my health in the past week.

“You’ve been getting up before dawn every morning, rushing to your computer to check the news. You haven’t been getting any sleep since you heard the rumors.”

I had been away from Myanmar for most of 2020, and the best I could do to stay connected to home was this pre-dawn ritual of checking every social media channel and every chat app the moment I woke up, to see if a military takeover had happened back home in Myanmar while I slept. Luckily, for all of January, I had been able to wake up to a sigh of relief. No coup… yet.

Manic thoughts had been occupying my head for weeks. No, they can’t do it, can they? Why would they do such a reckless thing?

Tanks on the streets, a press conference with stacks of supposed evidence of election fraud, the ultimatums that army chief Min Aung Hlaing had supposedly sent to Aung San Suu Kyi. All of that was politicking and posturing, right?

After all, the days when we had to cower before anyone who wore a green uniform, when we were almost completely cut off from the rest of the world, when the only way to access opportunities in life was to be in the favored circles of some high ranking military official — those days were long gone, right? Good riddance, we said, collectively, as we cast our ballots in 2015, for the first time in our lives.

We danced in the streets when the NLD won. They were our folk heroes.

We didn’t realise that they didn’t know what they were doing. They found it hard to transition from the brave activists who kept all our hopes alive in the junta years to become effective policymakers who would bring those hopes to fruition. A rocky five years ensued.

Regardless, we doubled down in 2020, braving a pandemic to vote again, to affirm that we were all in on the hopes of a better future. We had just barely gotten the hang of having the voice and agency to determine our own futures, and there was so much ground to cover, so many broken things about our country and our society that we had to fix. Who had the time to look back at that dark past we had left behind?

We are always in such a rush to get to a better future, that we neglect the ghosts of the past. I had been reading Thant Myint-U’s The Hidden History of Burma over the Christmas break in 2020. To my surprise, when reading the chapters that covered the early 2000s, I could feel the everyday fears that we used to live with creeping back into my body in a most visceral way. The propaganda songs that we used to watch nightly on grainy TVs played in my head. I could hear elders telling me to stay away from vices like drugs and political activism — but especially the latter, because that was the most dangerous thing a young person could do. I felt the lump in my throat I had during every encounter with a government official, who could arbitrarily determine the course of my life.

The body remembers trauma. As much as we might like to forget that it is there, it continues to haunt us. Looking back to January 2021, I think my sleeplessness was an almost instinctual shift into fight or flight mode, a bodily reaction to a fear that my mind was still not ready to accept.

We made awkward jokes that made light of the situation, because humor was the only way we really knew how to deal with it.

My colleagues in Myanmar over a work call: “If there's a coup and they cut off the internet over the weekend, please submit this proposal without us.”

A Facebook status from a journalist friend: “Tired and going to bed now. Going to sleep in tomorrow. Don’t wake me up unless there’s a coup.”

Then I woke up that morning on the first of February, way before the break of dawn, and all the ghosts of the past came rushing back.

Looking back now, I understand what it means to have collective trauma.

It is the saddest thing to know that any random person standing next to me in Myanmar, on a bus, in a queue at the voting booth, or at a protest, can instantly bond with me over this thing that they most definitely remember in their bones, but are wishing so hard to forget.

If there is any chance for us to bring our aspirations for our country to fruition, we need to find something other than ghosts to unite us.

What has given me the most hope in the year since the coup, with its protests, resistance and endless sacrifices, is the development of a collective identity for all of us that is inclusive and progressive.

That is largely thanks to a new generation in Myanmar who grew up connected to the world, who have no qualms about speaking their minds. They are savvy enough to see past our culture’s prevalent dogmatic beliefs and prejudices. They didn’t have to imagine what a life where you had control over your own destiny looked like, because they were already well on their way to controlling their own destinies — until the coup wound the clock back by several decades overnight.

The Gen Z kids who came of age during the 2010s don’t have the same trauma as the rest of us. However flawed the years of semi-democracy were, they gave a generation of Myanmar youth something from their past that they want to fight to reclaim and progress beyond, instead of hide and forget.

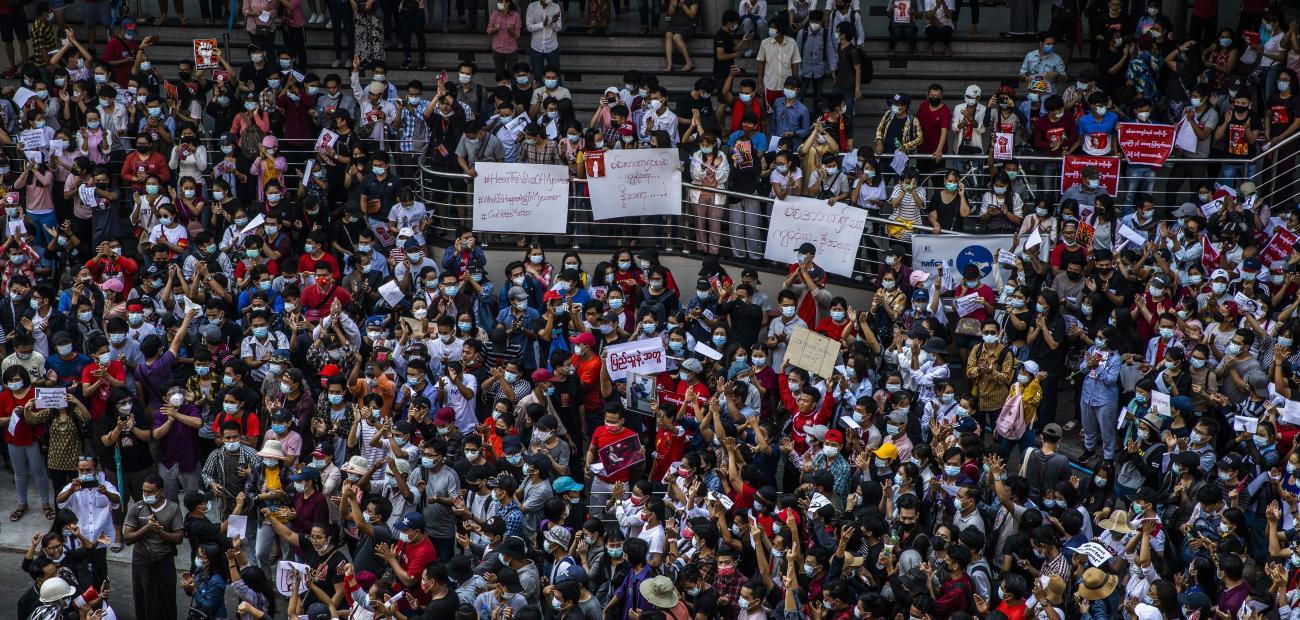

As outraged protests surged onto the streets in the weeks after the military seized power, young people turned defiantly to face the threats and violence of the soldiers.

“You messed with the wrong generation,” their slogans said.

Artwork courtesy of Raise Three Fingers.